Private Investing, “Selection Effects” and the Best Sushi Chef in Tokyo

by Caitlyn Driehorst

Caitlyn Driehorst is a financial advisor at RightWise Wealth, as well as the firm's founder and CEO. Caitlyn began her career at the Boston Consulting Group and held strategy roles at MGM Resorts, Capital Group American Funds and two venture-backed wealth startups. She holds a B.A. from the University of Chicago and an M.B.A. from UC Berkeley's Haas School of Business.

Published: December 8, 2025

If you’ve been watching the headlines, you’ll see evidence of the trend of increasing public access to private investments:

Current administration looking to add private equity options to 401(k) plans

Private credit marketplaces showing some disappointing results after heavy marketing to investing public

“Invest like Jay-Z” advertisements for investing in art, wine and more

Charles Schwab acquires Forge, a secondaries marketplace

Morgan Stanley acquires EquityZen, another secondaries marketplace

A great way to understand “selection effects” and private investing? Tokyo’s famous fish markets

On one hand, this seems like a positive trend as we’ve seen public markets grow increasingly concentrated, and private companies stay private longer: Amazon’s market cap was $560M at IPO, whereas today we see firms like Coinbase wait until they can achieve a double-digit billion market cap at IPO ($85B for Coinbase’s 2021 IPO) or stay private indefinitely (Stripe’s latest valuation is $105B.) Access to such private opportunities can sound like it’s leveling the playing field.

However, whereas public markets boast equal access to information and buying / selling, private investments are typically opaque and access is tiered.

Why is this important? Because when it comes to private investments, “average” returns are misleading. Results for private investments are typically not “normal,” or centered around a mean. Instead, results are “skewed left,” or concentrated in top performers.

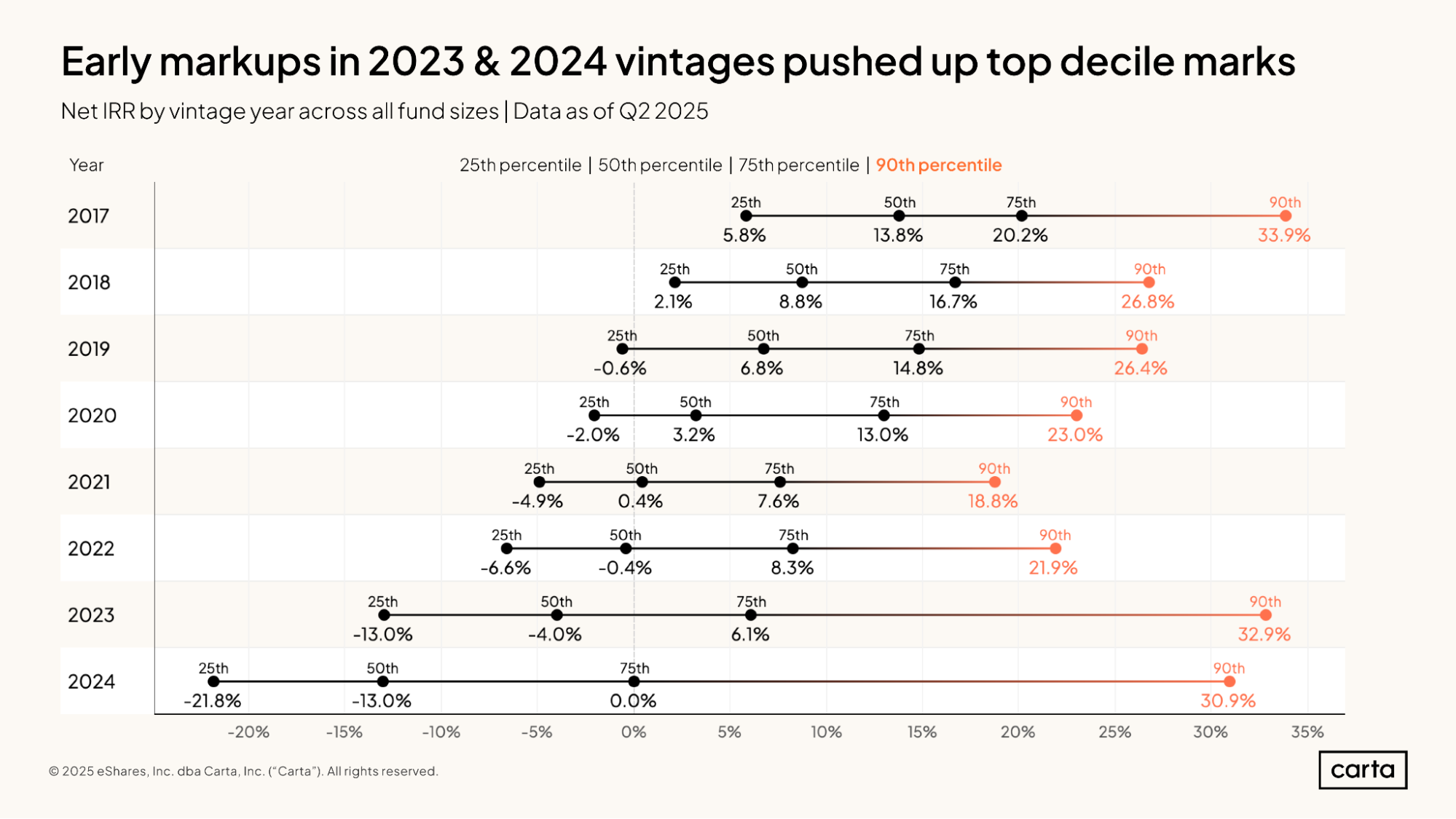

Consider this illustration from Carta’s 2025 VC fund performance report, showing the dramatic performance differences between “average” and top funds:

Why does this mean that public access to private investments may not be all its cracked up to be? It’s called “the selection effect.”

Perhaps you, like many of the men I met on OKCupid in the 2010s, watched the documentary “Jiro Dreams of Sushi.”

In this documentary, we go with Jiro – the best sushi chef in Tokyo – on his morning walk to the Tokyo fish market. Hours before it opens, Jiro has his pick of the best fish from every catch. Then, his rival, the second-best sushi chef in Tokyo, walks around and he gets the second pick of all the fish. All of the restaurants circulate the market, picking the best fish.

Only then, hours later, does the fish market open to the public.

Private markets are similar. Institutional investors see opportunities first. These include large pensions like CALPERS, university endowments, sovereign wealth funds, and the family offices of the richest families. Before anyone else sees the chance to invest in a VC fund or a private equity fund, these massive and professionalized shops review open deals, often with incredible access to information: in-person pitches by portfolio managers, detail on historic returns, pitch decks, and triangulation from highly-paid investment consultants. (This level of information is often not available to individuals investing smaller, more ad hoc amounts.)

So what trickles down to you and me, the hoi polloi for whom $100,000 isn’t necessarily a “small check”? All the fish that these master sushi chefs passed on. And why is that important? Because, as we saw earlier, there can be a huge difference between “the best” and “average” when it comes to private investment opportunities. When top opportunities are picked off by top investors, what’s left is meaningfully worse than initial “averages” would suggest.

Of course, there are exceptions to this effect. Not all private investments available to individuals are necessarily worse than average.

Institutions may pass on outstanding opportunities because their minimum check size would overwhelm the fundraise of a smaller, exciting raise (“capacity constraints”) whereas these opportunities may still be exciting for an individual.

Individuals may also have preferred access to certain opportunities via professional connections: for example, Bain consultants may have preferred access to Bain private equity funds, or founders may carve out part of a fundraising round for angels they know socially or believe could be otherwise strategic to the firm.

But especially where we see privates marketed heavily to everyday investors to place small amounts, I worry that marketing will promise sashimi – and deliver chum.

You don’t have to make decisions about your investments alone. Consider working with an independent financial advisor to spot-check your thinking, and place your decisions in the context of your broader financial plan.

Reach out today to meet with a RightWise advisor.